British Press Control during the ”Great Palestinian Revolt" -1936-1939.

Endangering the public peace could suspend newspapers

Arab defiance of the Palestine Mandate (British rule formalized by the League of Nations) over parts of the Levant (countries to the east of the Mediterranean) resulted in riots in 1929. The Shaw Commission (Report of the Commission on the Palestine Disturbances of August 1929)1 blamed in part:

“Excited and intemperate articles which appeared in some Arabic papers, in one Hebrew daily paper and in a Jewish weekly paper published in English and Propaganda among the less-educated Arab people of a character calculated to incite them.”

A new press law drafted by the Palestine administration provided punitive powers to confiscate press machinery. Newspapers could be suspended if deemed by the authorities to have published anything 'likely to endanger the public peace'. In addition, the ordinance introduced a new and extraordinary provision for government propaganda, by obliging newspapers to print immediately, textually and free of charge, all official communications and denials sent for publication.2

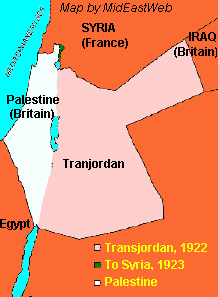

The nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs (1936-1939) against the British administration of the Palestine Mandate was a demand for Arab independence and the end of the policy of open-ended Jewish immigration to establish A "Jewish National Home."3

The Palestine administration instituted a number of administrative and legal steps to increase press control. It reorganized the Press Bureau to keep a careful watch on the local press and to cultivate closer working relations with editors and journalists. It provided information, access to official events and press facilities to officially 'recognised journalists' another form of press control, with potential threat of the withdrawal of press privileges.4

Censorship operated in the dark: the regulations made it a specific offence to reveal details of confidential censorship orders issued or to publish any statement or inference that 'any alteration, addition or omission' had been made by the censors.5

The successful clamp-down on independent press reporting of 'incidents' was part of the British military effort to put down the Arab rebellion. It also helped to conceal the more brutal methods used by the security forces to protect their image.

Controlling press reports going outside the country was challenging. Censorship of press cables in European languages, Arabic and Hebrew was imposed on 19 April 1936. Some correspondents got around telegraph censorship by telephoning Cairo and Beirut. Authorities placed restrictions telephones. Telephone subscribers would have to sign an undertaking not to transmit abroad messages containing news for press publication.

During the clamp-down on the Arab leadership in October 1937, telephonic communication with the neighbouring countries was cut off and all cable messages were scrutinized.

Foreign correspondents complained about the slowness of the authorities to verify news and limited hours in which the censor was on duty. In response to a charge from United Press that censorship arrangements favoured Reuters, such complaints were said to be due to an 'inefficient' reporter 'seeking to excuse his deficiencies' after being beaten by a 'more able competitor.'6

Access to military operations was provided in the autumn of 1938 perhaps because they enabled the authorities to control what was being reported. It was specified that there should be no mention of demolitions until they had taken place and then too 'in an unsensational manner and giving the reason for the demolition'. Other subjects generally banned were: reports of military operations before they occurred; the use of Jews in operations; the use by rebels of mosques for storing arms and shooting; and rebel proclamations that might alarm relatives in Britain of civilians and soldiers.

In October 1938 foreign correspondents were invited to witness and photograph the British operation to recapture the rebel-controlled Old City of Jerusalem. A party of British and American newspaper and cameramen were taken by the British military to observe a large operation to 'clean up' in Galilee. In the village of Mi'ar, this included a full view of the punitive wide-scale blowing-up of houses; A British Movietone newsreel explained the need for 'reprisals', after shots had been fired from Mi'ar at troops and 'the villagers declined to surrender the culprits or the rifles'.

Yet, despite military guidance and censorship there always remained an element of risk in inviting the press on board. The Daily Telegraph described how their convoy was preceded on its way to Mi'ar by a 'mine-sweeper' taxi, as the troops called a vehicle in which Arabs, said to be captured rebels, were 'carried as hostages to avert the mining of our route'.7

German newspapers charged British censorship in Palestine with concealing the truth of what was happening and being 'incompatible with the freedom of the press, which is so greatly praised in London.8

The Arab Revolt came to close in the summer 1939, but press control and repression was not relaxed. A new censorship order forbade any mention of Haj Amin al Husseini.9 The mufti's name mostly disappeared from newspaper pages and only the rarest mention would be allowed of his pro-Axis activity during the war years.

On 28 August, five days after the announcement of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, censorship was announced on all postal messages and telegrams to and from the country, as in all territories of the British Empire. On 3 September, the day Britain declared war on Germany, the Public Information Office announced full pre-publication censorship on all press content in Palestine.10

Censorship in wartime Palestine became notable for its strictness. Though somewhat relaxed in September 1945, the combination of pre-publication censorship and occasional suspension would remain a British administrative instrument until the end of the Mandate. The impact of the Press Ordinance and 'Emergency regulations' did not end even then. Both were adopted by the State of Israel soon after its establishment in 1948, carrying a legacy from British imperialism into the relations of the Israeli government with the local and foreign press.11

Wagner, Steven. Statecraft by Stealth : Secret Intelligence and British Rule in Palestine . Ithaca ;: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Goodman, Giora. “British Press Control in Palestine During the Arab Revolt, 1936-39.” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 43, no. 4 (2015): 699–720.

Ghandour, Zeina B. (10 September 2009). A Discourse on Domination in Mandate Palestine: Imperialism, Property and Insurgency. Routledge.

Ibid., Goodman.

Taylor, Philip M. British Propaganda in the Twentieth Century: Selling Democracy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999.

Ibid, Goodman.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Elpeleg, Zvi, and Philip Mattar. 1995. "The Grand Mufti: Haj Amin al-Hussaini, Founder of the Palestinian National Movement". The Middle East Journal. 49 (1): 150.

Ibid. Goodman.

Ibid.

I made a deep study of the establishment of the Israeli state in Palestine manny years ago.

It was an open secret that this was a tragic and unlawful event by the western powers to steal land that was not theirs and grant ownership to another people who had been wronged, not by Palistinians, or any Arab states, but by the German Nazi Reich.

What ever Jews once lived in Palistine for centuries past had in the main become Muslim, although there were small enclaves if Christian Palistinians living in peace with the Muslims.

The radicalization of Islamists had roots in valid grievances.

This too was a part of the Rhodes - Milner plan to dominate the world with British culture, this time by proxy, by importing Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe to the 'Holy Land'. Their heritage is obvious in their fair skin and light eyes and hair.

This is the tragedy of Zion.

\\][//