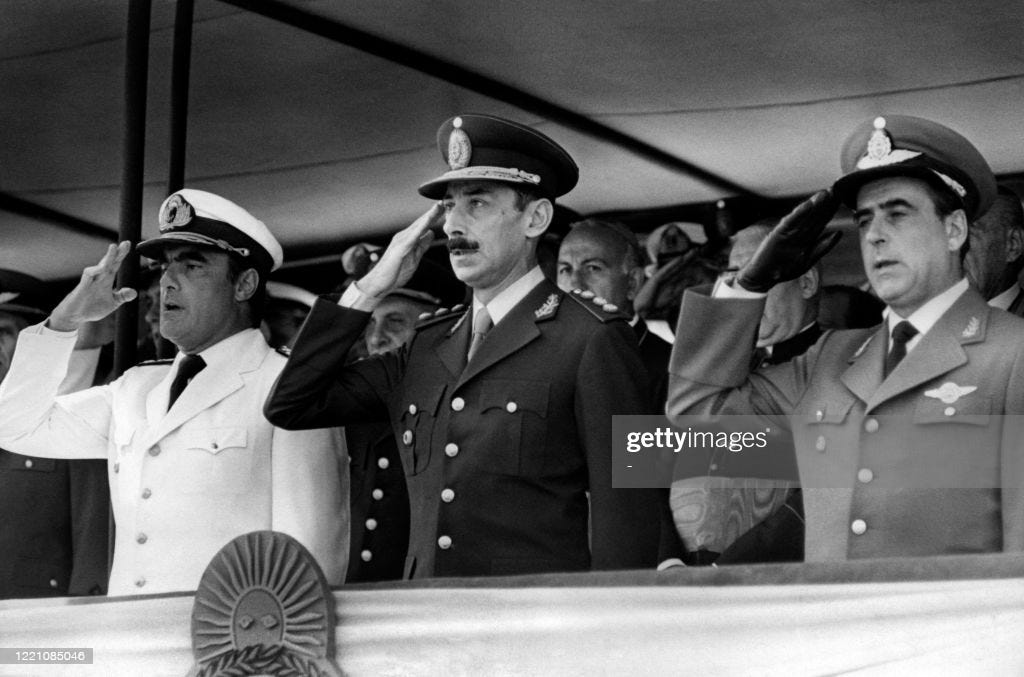

Military Censorship in Argentina: 1976-1983. "The Official Story."

24 tons of books burned; thousands of people detained, tortured, murdered or disappeared.

The Official Story (Spanish: La historia oficial) 1985 Oscar winning Best Foreign Language film from Argentina was made and released shortly after the return to democracy and the establishment of human right commissions to investigate the abuses carried out by the Military Junta (1976-1983).1

The movie’s central character lives in a “bubble of middle-class contentment and privilege” while thousands of people were detained, tortured, murdered or disappeared.

The Association of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo were the first major group to organize against the Argentina regime's human rights violations.

The little known context of military censorship in Argentina from 1976-1983 (to people in the United States) is outlined in the essay below.

The summary was prepared by a colleague using Argentine sources.

Argentina’s 1976-1983 Dictatorship: Book Burning

The Military Junta2 that governed Argentina after the coup of March 24th 1976 and until December 1983 implemented concerted efforts to censor literature that was deemed “subversive.” When military operation groups conducted clandestine raids in homes of suspected subversive people and political opponents, they would ransack belongings and look through the books in their home’s personal libraries. Finding certain authors and titles contributed to their decision to take the person with them. Many of those kidnapped in this manner became part of the “desaparecidos” (the disappeared).

In addition to personal libraries and home raids, there was a concerted effort to censor literature that was deemed leftist, subversive, or damaging to values such as God and Country. There are several events that took place with the specific intention of destroying copies of titles considered dangerous. According to Invernizzi3 the military government spent many resources in organizing this process. Censorship was centralized and controlled by the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and it was a very detailed, simple, and efficient process. Titles were analyzed and scrutinized by smart and prepared intellectuals and professionals.

Most of the titles were included because of the potential conclusions the reader would extract from them or because they were examples of critical thinking.4 Many children’s books were included in the banned lists, basically because they “questioned sacred values like family, religion, or country.” 5

Book burning known events:

· In July 1976, the Junta designated an “interventor” to the university press Eudeba (Editorial de la Universidad de Buenos Aires) who turned over to the Army 90,000 volumes of books. These were burned in the Palermo site of the 1st Army Corps (Primer Cuerpo del Ejército).6

· Also in 1976, Major General Luciano Benjamin Menéndez organized a massive book burning in the city of Córdoba, site of the 3rd Corps of the Army. Works by

Julio Cortázar,

Gabriel García Márquez,

Mario Vargas Llosa,

Marcel Proust, and

Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince were among them.

Menéndez was quoted by the local press as stating: “To the end that no parts are left of these books, pamphlets, magazines… so that our children can’t continue to be misled. We destroy with fire the damaging documentation that affects the intellect and our Christian lifestyle”7

· “In 1977 in Rosario, thousands of books from the Constancio Vigil People’s Library [Biblioteca Popular] were burned and all users investigated” 8

· On June 26, 1980 a Court order was issued that literature published by the Latin American Publishing Center (Centro Editor de América Latina – CEAL) of which Boris Spivacow was Director, needed to be burned. The burning took place in an open field in the city of Sarandí (7 miles south of the Capital). Spivacow was forced to observe the burn, as well as a photographer and other employees from the publishing company. Among the material burned that day there were works by Marx, Perón, and Che Guevara, but also books about science, history, and economics.9 According to author Graciela Cabal, the books took three days to burn, since some of them had been piled up and were damp. Her work was included as part of an encyclopedia for youth.10

Direct Quote:

“El destino final de muchos libros prohibidos era, entonces, arder en un pozo, en una hoguera común. Aunque hubo muchos otros casos, la quema de libros más grande de la dictadura argentina, o sea, la paradigmática, fue la que sufrió el Centro Editor de América Latina, que había fundado Boris Spivacow. El 30 de agosto de 1980 la policía bonaerense quemó en un baldío de Sarandí un millón y medio de ejemplares del sello, retirados de los depósitos por orden del juez federal de La Plata, Héctor Gustavo de la Serna”

Translation (by colleague):

“The final destination of many banned books was, therefore, to burn in a hole, in a common firepit. Although there were many other cases, the biggest book burning of the Argentine dictatorship, that is the most paradigmatic, was the one suffered by the Centro Editor de America Latina, founded by Boris Spivacow. On August 30, 1980, police from the Buenos Aires province burned one million and a half volumes from that publisher in an open field in Sarandí, titles that had been taken from the publisher’s warehouse by order of La Plata’s Federal Judge Hector Gustavo de la Serna.”

MacWilliam, Nick. The Official Story – The Film That Lifted The Lid On Videla’s Argentina. Sounds and Colors. May 22, 2013.

Ruffa, F. (2006, March 22). “La censura y quema de libros durante la dictadura militar” [Censorhip and book burning during the military dictatorship]. ANRed. https://www.anred.org/2006/03/22/la-censura-y-quema-de-libros-durante-la-dictadura-militar/

Ibid.

Guevara, A.A. & Molfino, M.R. (2005). La censura y la destrucción de libros en el último gobierno de facto (1976-1983) [Censorship and the destruction of books in the latest de-facto government (1976-1983)]. IV Jornadas de Sociología de la UNLP, 23 al 25 de noviembre de 2005, La Plata. La Argentina de la crisis: Desigualdad social, movimientos sociales, política e instituciones.Memoria Académica. http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/trab_eventos/ev.6579/ev.6579.pdf

“Hace 35 años, la dictadura ordenaba quemar 24 toneladas de "libros subversivos" [35 years ago the dictatorship ordered to burn 24 tons of ‘subversive books’]. (2015, June 25). Telam News Agency.

https://www.telam.com.ar/notas/201506/110322-dictadura-quema-libros-subversivos-aniversario.php

Arrigoni, M. & Bordat, E. M. (2011). Cultural repression and artistic resistance: The case of last’s Argentinean dictatorship. European Consortium for Political Research: Reykjavik 2011. Section 20, Panel 115. https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/2ce5bf42-f7b6-447a-8848-f3877f825938.pdf also Guevara & Molfino, 2005; “Hace 35 años”, 2015 as cited above.

Arrigoni & Bordat, 2011.

“Hace 35 años”, 2015.

Ruffa, 2006.

I recall thinking at the time that we were fortunate that some of the burned books had been translated into other languages and undoubtedly survived in other countries. The memory prompted other thoughts: translation of books today pays a pittance, and few understand the work involved in capturing nuance; the proliferation of electronic books and records actually makes it easier to censor them, simply by over-writing them with an approved updated version; Amazon's de facto monopoly on electronic books grants it censorship capability never before seen.

Every e-book downloaded from Amazon results in a potential Trojan Horse residing in my electronic devices. Amazon tracks who downloaded what books and individual reading progress in those books. Just a year ago it would have struck me to look for tin-foil hats should someone mention backing up all downloads to an inert device such as a thumb drive or DVD to prevent some nebulous group from changing or eliminating content. Now, I'm actually considering it. Amazon has aligned itself with Big Tech supporting censorship. Scary.