The horror of indescribability

Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890 – 1937) was an American writer of weird, science, fantasy, and horror fiction.1 Lovecraft’s work shows that “reality is more than what it seems to be, in that the desire for knowledge can act as a spark leading to a successful ascension towards the divine or the supernatural.”2

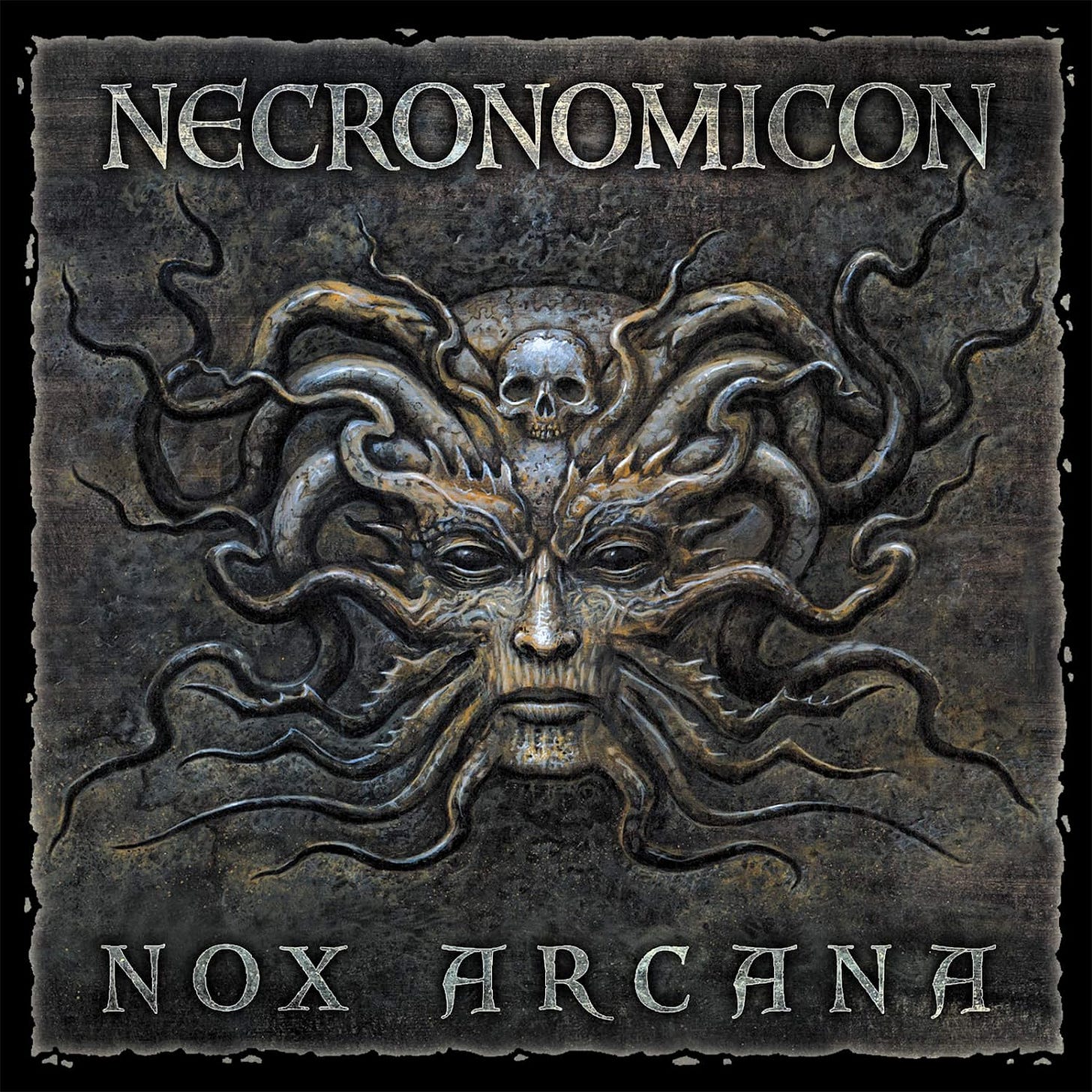

The Necronomicon

The Necronomicon is an imaginary tome of occult lore by the “mad Arab Abdul Alhazred” referenced by H.P. Lovecraft in 13 of his stories. Many people assume not only that it is an actual ancient text but that reading it leads to spiritual danger and criminal behavior.

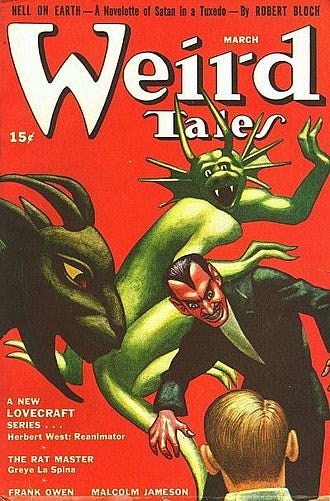

Lovecraft was part of a circle of authors, many of whom published in the magazine Weird Tales,3 who shared one another’s invented entities in their stories.

The Necronomicon appeared in the stories by Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch, Clark Ashton Smith, and others and also in stories by writers who paid Lovecraft to revise their work.

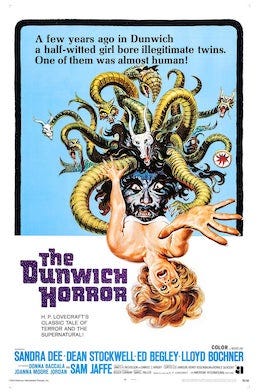

The Dunwich Horror

Lovecraft’s 1928 story, “The Dunwich Horror,”4 is a core story in the Cthulhu Mythos.5 Wilbur Whateley, deformed and unstable with an unknown father goes to Miskatonic University Library6 in search of the Necronomicon. . When the librarian, Dr. Henry Armitage, refuses to release the university's copy to him (and by sending warnings to other libraries thwarts Wilbur's efforts to consult their copies), Wilbur breaks into the library under the cover of night to steal it. A guard dog, maddened by Wilbur's alien body odor, attacks and kills him with unusual ferocity. When Armitage and two other professors, Warren Rice and Francis Morgan, arrive on the scene, they see Wilbur's semi-human corpse before it melts completely, leaving no evidence.

The story was made into a movie in 1970 starring Sandra Dee, Dean Stockwell, and Ed Begley.

A History of the Necronomicon

In 1936, Lovecraft wrote a 700-word piece entitled “A History of the Necronomicon,” describing its translations into various languages, which libraries own copies, and even a fictitious papal ban on the book. “This, coupled with the use of the Necronomicon in fiction of varying conviction by Lovecraft and other writing members of the Lovecraft Circle, served as virtually an invitation to hoaxers to build a legend.” 7

Necronomicon hoaxes abounded. Phony index cards were snuck into library catalogs at Yale and the University of California.8 . One hoaxer even constructed a fake Necronomicon that was displayed in a glass case in Brown University’s library, where the bulk of Lovecraft’s letters are archived.9

People wrote Necronomicons. The first “Necronomicons” were penned as early as the 1950s. Lovecraft’s publisher, August Derleth ), read these early editions and reported that they were merely recycled incantations from widely published magical grimoires sprinkled with references to Lovecraft’s mythos. Many “Necronomicons” have subsequently been written; however, the three most famous are the so-called de Camp-Scithers, Hay, and Simon “Necronomicons.”10

The Simon Necronomicon (1977) was 666 leather-bound copies and 1275 cloth copies published before Avon produced its paperback edition in 1980.11 Whereas Scithers and Wilson admitted their “Necronomicons” were made in jest, “Simon”– a pseudonym used by the editor– has insisted that his Necronomicon is authentic.12

The John Hay Library at Brown University is home to the largest collection of H. P. Lovecraft materials in the world.

craziest literary afterlife

Lovecraft’s is perhaps the craziest literary afterlife this country has ever seen.13

Lovecraft ranks among the most tchotchke-fied writers in the world. Board Games. Coins. Corsets. Christmas wreaths. Dice. Dresses. Keychains. License-plate frames. Mugs. Phone cases. Plush toys. Posters. Ties. Enterprising fans have stamped the name “Cthulhu” (Lovecraft’s most famous creation; a towering, malevolent, multi-tentacled deity) or other Lovecraftian gibberish on nearly every imaginable consumer product. And it’s not just merchandise. It’s apps and movies and podcasts.

After Engulfment: Cosmicism and Neocosmicism in H. P. Lovecraft, Philip K. Dick, Robert A. Heinlein, and Frank Herbert. By Ellen J. Greenham. New York, NY: Hippocampus Press; 2022.

Bogiaris, Guillaume. “‘Love of Knowledge Is a Kind of Madness’: Competing Platonisms in the Universes of C.S. Lewis and H.P. Lovecraft.” Mythlore 36.2 (132) (2018): 23–42.

Weird Tales is an American fantasy and horror fiction pulp magazine founded by J. C. Henneberger and J. M. Lansinger in late 1922. The first issue, dated March 1923, appeared on newsstands February 18.

Full text available at The Dunwich Horror - Wikisource, the free online library.

Price, Robert M. (1990). H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos. Mercer Island, WA: Starmont House.

Derleth, August. “The Making of a Hoax.” In The Dark Brotherhood and Other Pieces, edited by August Derleth, 262–7. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House, 1966.

There is a Wikipedia page devoted to the fictional Miskatonic University and its faculty.

Price, Robert M. “Hexes and Hoaxes: The Curious Career of Lovecraft’s Necronomicon.” Twilight Zone Magazine (November–December1984): 59–65; Laycock, Joseph P. “How the Necronomicon Became Real: The Ecology of a Legend.” The Paranormal and Popular Culture. 1st ed. Routledge, 2019. 184–197.

Derleth, August. “The Making of a Hoax.” In The Dark Brotherhood and Other Pieces, edited by August Derleth, 262–7. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House, 1966

Price, Robert M. “Hexes and Hoaxes: The Curious Career of Lovecraft’s Necronomicon.” Twilight Zone Magazine (November–December1984): 59–65.

Laycock, Joseph P. “How the Necronomicon Became Real: The Ecology of a Legend.” The Paranormal and Popular Culture. 1st ed. Routledge, 2019. 184–197. De Camp, L. Sprague. Lovecraft: A Biography. London: New English library, 1975;

Simon. Necronomicon. New York: Avon Books, 1980.

Simon Simon. 2006. Dead Names : The Dark History of the Necronomicon. Burton Mich: Subterranean Press. Simon claims that he encountered a Greek manuscript of the Necronominon in 1972. The text had been stolen from an unnamed library by Steven Chapo and Michael Huback, two Orthodox priests who used their office to gain access to university libraries in order to steal rare books for sale on the black market. Simon translated the text and published it with the help of other individuals, all of whom had some connection to The Warlock Shop, a famous occult store run by Herman Slater in Brooklyn Heights. In 1976, Slater moved his shop to Chelsea and renamed it the Magickal Childe. The shop was originally the sole distributor of the Simon Necronomicon. In Dead Names, Simon explains that the indi-vidual who showed him the manuscript likely burnt any stolen books after Chapo and Huback were arrested, thus explaining why no one has ever seen the original Greek manuscript. For more on this see Laycock, Joseph P. “How the Necronomicon Became Real: The Ecology of a Legend.” The Paranormal and Popular Culture. 1st ed. Routledge, 2019. 184–197.

Eil, Philip,” The Fantasy Author H.P. Lovecraft at 125: Genius, Cult Icon, Racist” The Atlantic (August 20, 2015).

"Human actions are as free and empty of meaning as the free movements of the elementary particles. Good, Evil, Morality, Feelings? Nothing but" Victorian fictions”. Only egoism exists. Cold, intact, and brilliant".-- Houellebecq on Lovecraft-1991.

I happen to be a fan. I read some of these stories as a kid and was attracted to a possible world, like LOTR. Imho, worth watching was Lovecraft Country. Anton LaVay just seemed to be for selfishness, if anything else.

The fact that Lovecraftian horror has made its mark around the world, shows its interest hasn’t waned.

Great choice to bring up. Though personally I wouldn’t place him on par with Philip K. Dick or Harlan Ellison.