Extra Illustrated Books: A Prelude to Wikipedia?

Grangerizing was a social pastime in 18th and 19th century England

What is Grangerizing (also known as “extra-illustration)?

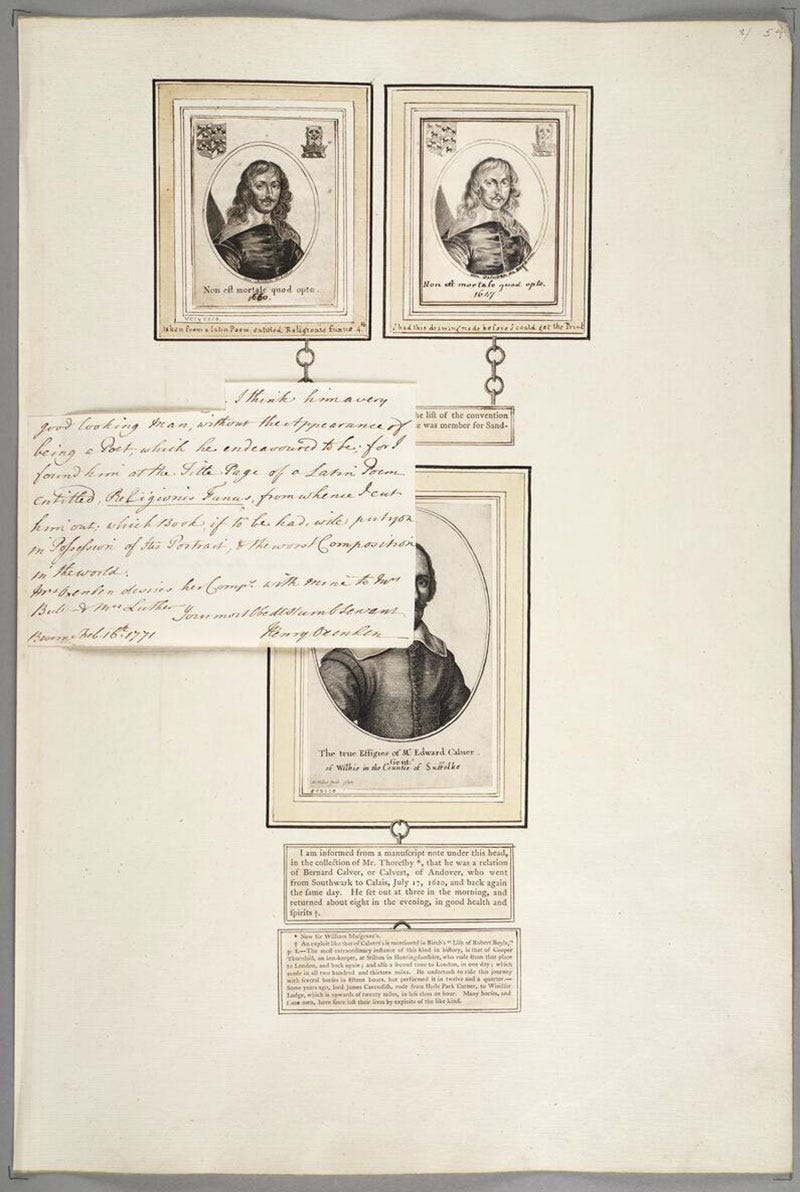

Altering books by placing images selected from one’s private collection alongside words written by someone else was a popular pastime in eighteenth-century England referred to as “extra-illustration” or “grangerization.”1 This activity allowed readers and book owners to insert new visual dimensions into their reading experience.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, an obsession spread among bibliophiles for extra-illustrating or grangerizing books.2 Readers would supplement the pages of an already published book by inserting prints and related materials acquired from other sources. This process would often result in a huge expansion of the original volume, a ballooning that could easily stretch the book to bursting, requiring rebinding into additional volumes to hold the interleaved material.3

The expression “to grangerize” is derived from the name James Granger, (1723–1776), a print collector who compiled A Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution (1769)4 as a catalogue of engraved historic prints. (Granger never actually practiced extra-illustration. It was the fact that his publication was the first book to be so altered that lent his name to the phenomenon).

Granger’s friend, Richard Bull (1721–1805), a member of Parliament and an avid collector, went well beyond using the book to find and procure the recommended prints for his collection. Instead, he dismantled and cut up Granger’s text, placing relevant passages with the corresponding engravings on large backing sheets that served as new pages, and then he bound all these pages together. This process radically altered and expanded the structure and contents of the original book.5

The practice of adding additional material spread throughout the late-eighteenth and early nineteenth century, developing from a social experience among a small cadre of print collectors in gentleman clubs into a private pastime enjoyed in the home.6

Grangerizers as Villains

Businesses cropped up dedicated to extra-illustration, such as Frederick Strong’s “The Destruction Room,” which opened ca. 1847. This was advertised as a place “full of interesting Books, or at least when cut up will be so …

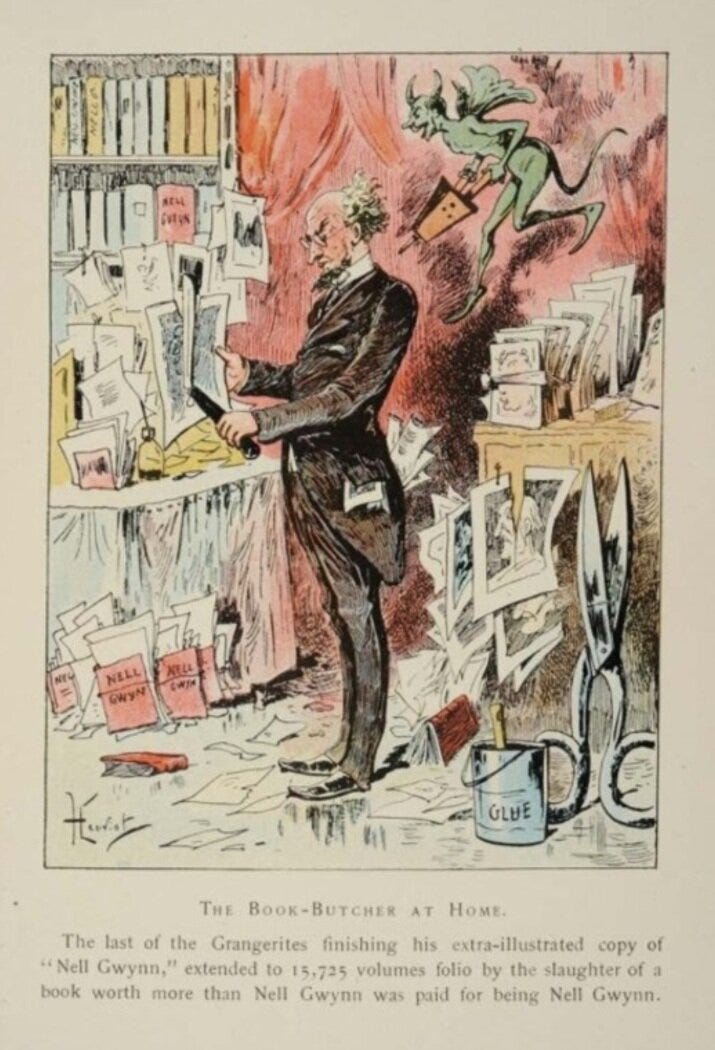

Regardless of its popularity, the act of grangerizing was under attack by critics by the 1880s. One critic characterized a grangerite as a ‘Book-Ghoul … who combines the larceny of the biblioklept with the abominable wickedness of breaking up and mutilating the volumes from which he steals.’ Another critic viewed the grangerite as “a sort of literary Attila the Hun or Genghis Khan, who has spread terror and ruin around him.”7 (see illustration at top of this essay about a Book Butcher).

“The Obsession with Extra-Illustrating Books” at The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens

The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, (The Huntington) is a collections-based educational and research institution established in San Marino, California.8 Among its extensive collection is the Bull Granger, the Kitto Bible, and almost 1,000 other extra-illustrated works—more than any other library. It was the site for the conference, “Extra Extra! The Material History of the Visually Altered Book,” in September, 2024.

Extra-Illustration and the Dream of the Universal Library.

Gabrielle Dean’s essay, “Every Man His Own Publisher’: Extra-Illustration and the Dream of the Universal Library” observes:

The hypertext book that reflects and facilitates social reading made a preliminary appearance in the late eighteenth century, thanks to an Anglican parson and amateur historian named James Granger. And an extension of Granger’s practice in the early twentieth century laid the groundwork for the modern full-text database.9

Dean notes, “The Grangerized or “extra-illustrated” book turned the linear text into a unique, multi-directional network of “links” to related texts, and recast the reader as the writer’s collaborator.”10 She concludes that “the basic impulse of the Grangerite—to gain intimacy, as a reader, with the author, subject, and “body” of the book, to the point of becoming a self-appointed co-author or publisher—is most usefully situated on a continuum of desire that is both much older than Grangerization itself and very contemporary: the dream of the universal library, which Wikipedia defines as a library “containing all existing information [. . .] all books, all works (regardless of format) or even all possible works”. 11

18th Century Extra-Illustrated Books: Book Talk by Julie Park.

Dr. Julie Park whose lecture is linked below is the Paterno Family Librarian for Literature and Professor of English at Pennsylvania State University. She is also the editor of the Penn State History of the Book Series at Penn State University Press.

[Section on “Extra-Illustrated Books” begins at 10:00]

“Grangerization” is the term applied to the practice that became fashionable in England towards the end of the 18th century of collecting portrait prints and adding them as extra illustrations to a text. It began after the Rev. James Granger published the Biographical History of England from Egbert the Great to the Revolution. Granger never actually practiced extra-illustration. It was the fact that his publication was the first book to be so altered that lent his name to the phenomenon. See the study: Facing the Text: Extra-Illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain, 1769–1840. By Lucy Peltz. San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library. 2017.

Facing the Text: Extra-Illustration, Print Culture, and Society in Britain, 1769–1840. By Lucy Peltz. San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library. 2017. Reviewed by Nicolas Barker in Library 2018: 245–247.

Julie Park and Adam Smyth. The Obsession with Extra-Illustrating Books. The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens. Sept. 24, 2024.

Granger, James, 1723-1776. A biographical history of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution. See copy at the Library of Congress here: https://www.loc.gov/item/50049842/

Julie Park and Adam Smyth. The Obsession with Extra-Illustrating Books. The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens. Sept. 24, 2024.

For the development of extra-illustration into a social, even familial, pastime see Lucy Peltz’s “The Extra-Illustration of London: The Gendered Spaces and Practices of Antiquarianism in the Late Eighteenth Century” in Producing the Past: Aspects of Antiquarian Culture & Practice 1700–1850, ed. Martin Myrone and Lucy Peltz (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999).

Tedeschi, Anthony. “Extra-Illustration as Exemplified in A.H. Reed’s Copy of Boswell’s ‘Life of Johnson.’” Script & print 36.1 (2012): 42–52

The Huntington. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens shares its world-renowned collections to support scholarship, foster learning, inspire creativity, and offer transformative experiences for diverse audiences.

Dean, Gabrielle. “‘Every Man His Own Publisher’: Extra-Illustration and the Dream of the Universal Library.” Textual Cultures 8, no. 1 (2013): 57–71. “In the twenty-first century, the age-old dream of a universal library seems within reach at last, due to an expanding digital environment. But in fact, the publishing and reading practices we associate with Web 2.0 have some very old precedents. One such practice is Grangerization, a bibliophile hobby that originated in the late eighteenth century. In this period, and throughout the nineteenth century, private collectors inserted various forms of ephemera into their books: prints, letters, manuscripts, receipts, clippings. The books were usually rebound to accommodate the additional pages of tipped- and pasted-in material. The Grangerized or “extra-illustrated” book turned the linear text into a unique, multi-directional network of “links” to related texts, and recast the reader as the writer’s collaborator”

Ibid., p. 57.

Ibid., p. 68.

I never heard of this practice. How very interesting! Thank you.

Wonderful post. I knew about these but never saw one. Thank you.