EPHRAIM CHAMBERS & Gravity's Rainbow

"father of the modern encyclopaedia throughout the world."

The individual’s cooptation by paranoia-inspiring bureaucratic structures

FROM THE OUTSET, the critical response to Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow has been strongly shaped by an interest in the politics of language. Pynchon’s exploration of language politics invites an array of questions, many involving the individual’s cooptation by paranoia-inspiring bureaucratic structures and the prospects for subversion of, or escape from, these forces. These questions frequently lead critics to consider the structure of the narrative itself and its political implications. As part of this process, the work has been read as an example of various genres, including historical novel, allegory, satire, comedy, war novel and jeremiad…Gravity Rainbow’s encyclopedism only come to light when one contextualizes Pynchon’s engagement of the genre by turning to the emergence of the modern encyclopedia, a moment of significantly new intellectual creativity and dissemination, as well as bureaucratization and cooptation. Gravity’s Rainbow invites us to read this historical “moment” as a version of chaotic strife that anticipates the “zone” of Pynchon’s post-war Europe. Prominent features of Gravity’s Rainbow -- its title, structure and dominant metaphor -- suggest that Pynchon is reading the novel’s most obvious historical context (World War II) through the rise of the modern encyclopedia, and through Ephraim Chambers’ ground breaking contribution, Cyclopaedia, or A Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1728) in particular.1

Ephraim Chambers-1680-1740 is Buried in Westminster Abbey

Heard of by many,

Known to few,

Who led a Life between Fame and Obscurity

Neither abounding nor deficient in Learning

Devoted to Study, but as a Man

Who thinks himself bound to all Offices of Humanity,

Having finished his Life and Labours together,

Here desires to rest--EPHRAIM CHAMBERS—2

Before there was Wikipedia there was Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopædia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences

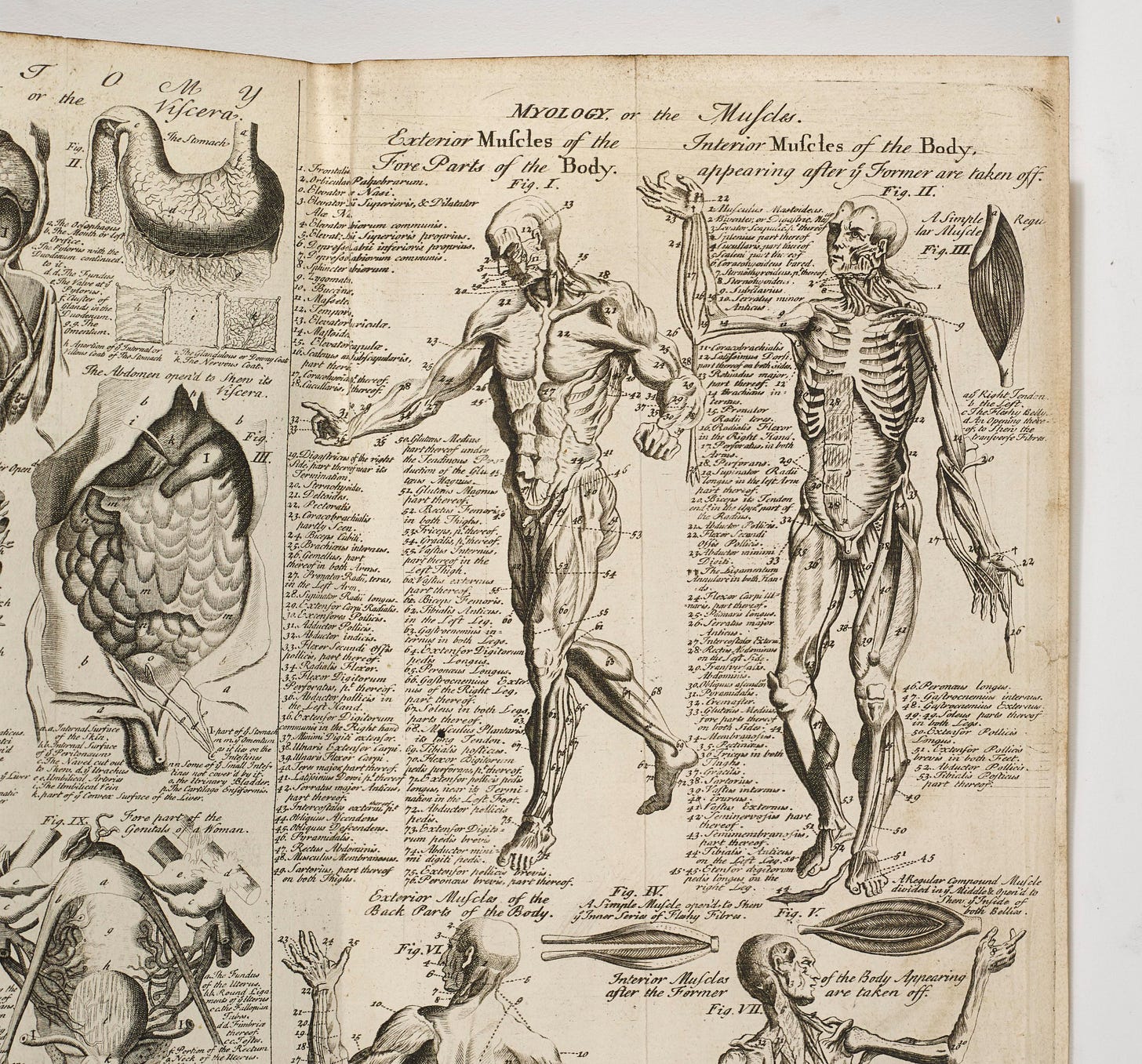

Cyclopædia: or, An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences; containing the Definitions of the Terms, and Accounts of the Things signify'd thereby, in the several Arts, both Liberal and Mechanical, and the several Sciences, Human and Divine: the Figures, Kinds, Properties, Productions, Preparations, and Uses, of Things Natural and Artificial; the Rise, Progress, and State of Things Ecclesiastical, Civil, Military, and Commercial: with the several Systems, Sects, Opinions, &c. among Philosophers, Divines, Mathematicians, Physicians, Antiquaries, Criticks, &c. The Whole intended as a Course of Antient and Modern Learning.

Chambers's Cyclopaedia in turn was the inspiration for the landmark Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot.

You can read the original Cyclopædia which has been digitized at the University of Wisconsin.3

In the preface to his Cyclopaedia published in 1728 Ephraim Chambers offers readers a systematized structure of his attempt to produce a universal repository of human knowledge. Divided into an interconnected taxonomic tree and domain vocabulary, this structure forms the basis of one effort from the Metadata Research Center to study historical ontologies.4

Gutierrez-Jones, Carl. “Encyclopedic Arc: Gravity’s Rainbow and Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia.” The international journal of the book 8.1 (2011): 19–29.

Nichols, John. “Memoirs of Mr. Ephraim Chambers.” Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press, 2014. 659–661.

Cyclopædia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences (2 Volumes) - UWDC - UW-Madison Libraries (wisc.edu)-Cyclopædia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences (2 Volumes) - UWDC - UW-Madison Libraries.

Scott McClellan, Mat Kelly, and Jane Greenberg. “Modeling Ephraim Chambers’ Knowledge Structure from a Naive Standpoint.” arXiv.org (2021): n. pag. Print.[2109.13915] arXiv:2109.13915 [cs.DL]

"Chambers's Cyclopaedia in turn was the inspiration for the landmark Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot."

Wondering why Chamber's used Cyclopaedia sans en- and Diderot used it, I dug around a bit. (I think I love Wiktionary even more than Wikipedia (particularly since I don't have an OED sub.).)

Which eventually coughs up (for the antique spelling): https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/encyclopaedia#Latin

"Latin - Etymology

From Renaissance Ancient Greek ἐγκυκλοπαιδεία (enkuklopaideía, “education in the circle of arts and sciences”), a mistaken univerbated form of ἐγκύκλιος παιδείᾱ (enkúklios paideíā, “education in the circle of arts and sciences”), from ἐγκύκλιος (enkúklios, “circular”) + παιδείᾱ (paideíā, “child-rearing, education”). This spelling seems to have been first used by Paul Skalich in 1559, although the spelling encyclopedia goes back to at least 1517, with a work by Johannes Aventinus. "

Wikipedia proper is a little more thorough: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Encyclopedia

"The word encyclopedia (encyclo|pedia) comes from the Koine Greek ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία, transliterated enkyklios paideia, meaning 'general education' from enkyklios (ἐγκύκλιος), meaning 'circular, recurrent, required regularly, general' and paideia (παιδεία), meaning 'education, rearing of a child'; together, the phrase literally translates as 'complete instruction' or 'complete knowledge'. However, the two separate words were reduced to a single word due to a scribal error by copyists of a Latin manuscript edition of Quintillian in 1470. The copyists took this phrase to be a single Greek word, enkyklopaedia, with the same meaning, and this spurious Greek word became the New Latin word encyclopaedia, which in turn came into English. Because of this compounded word, fifteenth-century readers and since have often, and incorrectly, thought that the Roman authors Quintillian and Pliny described an ancient genre."

So... 'Encyclopédie' is the 'right' form of the wrong (univerbated) form of the two Greek words and Chambers just decided to drop the En- for Reasons. (I could see rationalisation that might make sense: if enkúklios is the Greek word but cyclus (-> cyclo-) is the 'right' form of the original ancient Latin borrowing of enkúklios then re-doing the mistaken univerbation might seem like the right thing to do, since the intended meaning of the portmanteau is the same as the mistaken univerbation. But I don't know if that's actually what he was doing.)

elm

learn something new everyday

I've read the Carl Gutierrez-Jones paragraph quoted above five or six times now and I can't make any sense of it. It's the strangest thing. There are six sentences in the excerpt. I know what all the individual words mean (although I did have to look up "cooptation") but I just don't get anything else. It's like reading Jabberwocky, but Jones clearly has some serious point to make and Kathleen, who is always precise, intentionally selected the paragraph. It's an odd sense, discomfiting even.

On a lighter note, I'd like to add that Pynchon is literature's greatest living book title writer. Gravity's Rainbow certainly has a place in the book title Hall of Fame, but my all time favorite is "The Crying of Lot 49." Even now, decades after I first unpeeled the magnificent dual meaning of those words they still burst like a grenade in my mind when I read them. Pynchon packed a poem into five words. It's amazing.

Regarding Encylopedias, it's odd from a modern perspective to consider a world where such a thing could even be considered possible or useful. This is true even though most people older than 40 (?) might have grown up in a home where an Encyclopedia lined a bookshelf. It's interesting to know that there is a Metadata Research Center where historical systems of organization, classification and their associated ontologies are studied. On the surface the existence of powerful, dynamic search technologies have changed has changed a lot of this, and AI promises to push yet another axis into the domain. Even so, consciousness itself has an organizing, classifying, ontology constructing nature. We each live in a kind of encyclopedia of our own making.