The Egyptian Hall was among the grandest of the commercial exhibitions operating in London in the early decades of the nineteenth century trying to satisfy the late Georgian appetite for novelty and spectacle. 1 There were many commercial museums at this time including the Mechanical Theatre (mechanical contrivances); the Eidophusikon (light and image scenes, like a storm at sea and a shipwreck); the Panorama (views in-the-round of events in Napoleon’s career); and the Royal Menagerie (exotic animals).

William Bullock: museum entrepreneur

William Bullock ( 1773 – 1849) was an English traveller, naturalist, museum entrepreneur and antiquarian. He came from a showman family: in their early life his parents had run a travelling waxwork. Bullock was planning a specially designed building on the south side of Piccadilly as a permanent museum, and the result was the famous Egyptian Hall, , with its exotic façade in the style of an ancient Egyptian Temple designed by Peter Robinson2 which opened in 1812. The façade of the Egyptian Hall was loosely based on the design of the Temple at Dendera, with two Coade stone statues representing Isis and Osiris.3

The collection included ‘upwards of Fifteen Thousand Natural and Foreign Curiosities, Antiquities, and Productions of the Fine Arts’.

Where did all these museum items—especially those of the Voyages of James Cook— end up?

There is a much scholarly literature devoted to analyses of natural history objects and collections. – not only in museum studies, history of science, and professional museum literature, but also in visual studies, anthropology and cultural geography. 4

Colonial acquisition routes—especially the voyages of James Cook—were the source of many items exhibited.5 Historians have detailed this traffic, including the activities of individual colonial officers (collecting as part of their official duties or otherwise), larger enterprises such as imperial geological surveys, and museum-making in colonial contexts.6 Tracking where these items ended up, especially those from the voyages of Cook has been the subject of much study. 7

Some objects that we know existed (because they were depicted by artists during the voyages or back in Britain) have not been located. Some have been lost for decades and then found and identified in collections where they would not have been suspected, such as the Maori carved panel found in Tübingen by Volker Harms (1998).8

From Museum to Magic

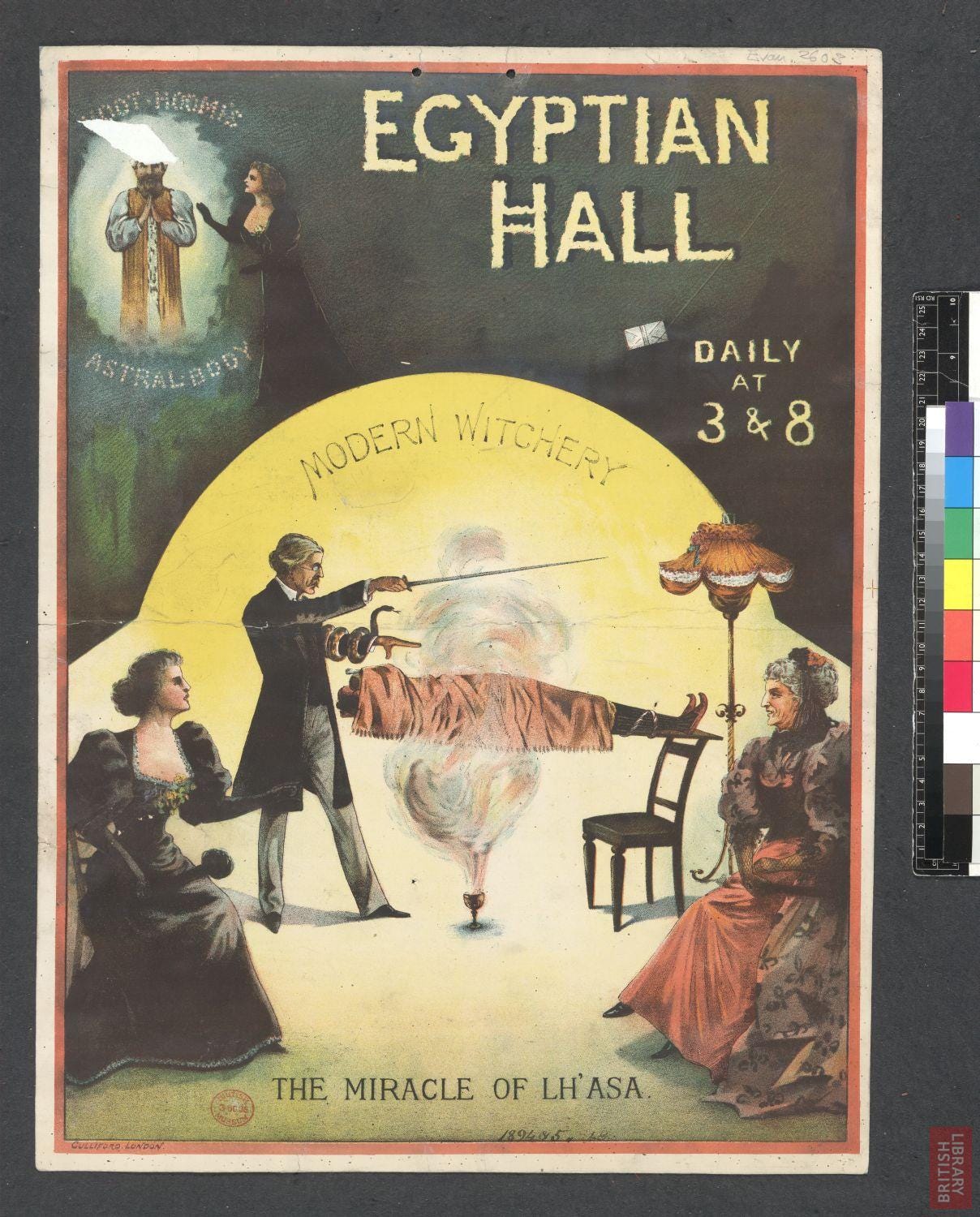

In 1819, Bullock sold his ethnographical and natural history collection at auction and converted the museum into an exhibition hall. For years it continued as an exhibition hall. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Hall was also associated with magic and spiritualism, as a number of performers and lecturers had hired it for shows. The Hall became known as England's Home of Mystery.9 Many illusions were staged including the exposition of fraudulent spiritualistic manifestations then being practiced by charlatans. The final performance was on 5 January 1905. It was then torn down.10

Pearce, S. M. (2008) ‘William Bullock: Collections and Exhibitions at the Egyptian Hall, London: 1816–25’, Journal of the History of Collections, 20, 17–35.

P. Robinson (1776-1858)), architect, was known as a connoisseur of exotic styles. The original ground plan for the Egyptian Hall survives: National Archives, CRES 6/11; for the architectural history, see Survey of London, vol. XXIV, St James’s, Westminster (London, 1960 online at http://www.british-history.ac.uk.

J. Curl, Egyptomania. The Egyptian Revival: A Recurring Theme in the History of Taste (Manchester, 1960).

Alberti, Samuel Constructing nature behind glass. Museum & Society 6 (2008).

James Cook (17281779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and to New Zealand and Australia in particular.

Bennett, T. (2004) Pasts Beyond Memory: Evolution, Museums, Colonialism, London: Routledge; Loughney, C. (2005), ‘Colonialism and the Development of the English Provincial Museum,1823–1914’, Ph.D., Newcastle University; Sheets-Pyenson, S. (1988) Cathedrals of Science: The Development of Colonial Natural History Museums During the Late Nineteenth Century, Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

“WILLIAM BULLOCK: Inventing a visual language of objects. By SUSAN PEARCE in Knell, Simon J., Suzanne. Macleod, and Sheila E. R. Watson. Museum Revolutions: How Museums Change and Are Changed. London;: Routledge, 2007; Kaeppler, Adrienne L. “Lost Objects, Questionable Localities, and Other Cook-Voyage Enigmas.” Pacific Arts 14, no. 1/2 (2015): 78–84.

Kaeppler, A. L. 1974. Cook Voyage Provenance of the “Artificial Curiosities” of Bullock’s Museum. Man, the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 9 “Artificial Curiosities” Being an Exposition of Native Manufactures Collected on the Three Pacific Voyages of Captain James Cook, R.N. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Special Publication 65. 2011.

England’s Home of Mystery. Taylor, Nik (2007) England's Home of Mystery. In: England's Home of Mystery, 17-18 December 2007, Milton Theatre, University of Huddersfield.

Cook was allegedly an ancestor on my paternal grandfather's side, although I was adopted. Heard this week from a fifth cousin in the West of England, but that's genetic, not through adoption.

We learned almost 50 years ago that adoptees marry one another, even adoptees who are unaware of the adoption,, at twice the statistically anticipated rate. My adoption was to a loving home; my sister was adopted four years later. My wife was adopted three years after me, was given up by Appalachian residents who could not afford to feed all their children. That was at a time of scarcity of children for adoption.

Oh, that's a cool postcard!

"J. Curl, Egyptomania. The Egyptian Revival: A Recurring Theme in the History of Taste"

Yeah. There's a book about that? Cool!

elm

mesopotamia always gets short-shafted