“Between 1856 and 1896 nearly two thousand German-language publications were permitted by Russian censorship only with the excision of certain passages, ranging in length from a single line to many pages.”1

The operations of the Russian Foreign Censorship Committee stopped books at the borders.

The Committee focused on:

disrespect for the Russian royalty,

opposition to the existing social order,

Russians as non-European barbarians2, and

ideas contrary to region and morals.

In the late 19th century, the French word caviar came to refer figuratively to the Russian censors’ practice of blotting out passages in newspapers and books with black ink, hence the French expression passer au caviar and the verb caviarder, which both mean to blue-pencil, to censor.

The censoring authorities banned sex in publications with particular enthusiasm (39.7 per cent); philosophy lost passages in about 16 per cent of their incoming items; history, religion and social-condition literature fell at the rate of 10–14 per cent 3

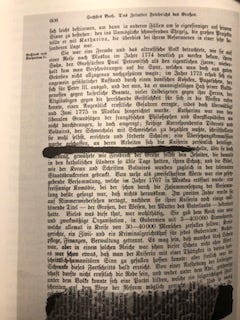

The censors smeared black ink over offending passages (‘caviar’ ) or pasted paper directly onto the page.4

The online exhibit, Watchmen at the Gates: Imperial Russian Censorship of Foreign Publications, provides an overview of the censorship policies of Customs, the Foreign Censorship Committee and the Postal Censorship— what kinds of mail and which recipients were affected, mail routing where appropriate, and a survey of the various foreign-newspaper-and-magazine censorship offices (FNMCOs) and their censor marks. The gates were Russia’s ports and inland border posts; the censors were her watchmen. 5

There aren’t any good images of the caviar or papering over on the Internet, so I took this picture with my phone from Choldin’s book.6

Choldin, Marianna Tax. A Fence Around the Empire : Russian Censorship of Western Ideas Under the Tsars . Durham [N.C: Duke University Press, 1985.

For background on perceptions of Russia by the West see: Taras, Ray. 2014. Russia's identity in international relations: images, perceptions, misperceptions. London: Routledge.

Galson, Peter. 2012. “Blacked-out spaces: Freud, censorship and the re-territorialization of mind.” The British Society for the History of Science 45(2): 235–266. June.

Ibid., Choldin

Watchmen at the Gates: Imperial Russian Censorship of Foreign Publications. On the website of The Rossica Society, a world-wide society devoted to all aspects of Russian philately, from the pre-stamp days of Imperial Russia to current post-Soviet philately. The purpose of the Society is to unite all philatelists throughout the world with an interest in Russian philately.

Ibid., Choldin, p. 140.

In the1990s I spent time in Saudi Arabia, where the same caviering occurred. It was so severe that we referred to USA Today as USA Yesterday.

This caviaring seems very labor- and focus-intensive. Censorship is mindless and effortless today. Heck, algorithms are going it seamlessly, without leaving a tell-tale blotch of black ink.