“Two Ariadne Threads through the Bibliographic Labyrinth"

The Sandars and Lyell Readerships in Bibliography”

Latin inscription : "HIC QUEM CRETICUS EDIT. DAEDALUS EST LABERINTHUS. DE QUO NULLUS VADERE. QUIVIT QUI FUIT INTUS. NI THESEUS GRATIS ADRIANE. STAMINE JUTUS", i.e. "This is the labyrinth built by Dedalus of Crete; all who entered therein were lost, save Theseus, thanks to Ariadne's thread."

“Two Ariadne Threads through the Bibliographic Labyrinth: The Sandars and Lyell Readerships in Bibliography”

Kathleen de la Peña McCook

Working Paper - 2025

ABSTRACT: This essay explores the bibliographic significance of the Sandars Readership in Bibliography (est. 1895, Cambridge University) and the Lyell Readership in Bibliography (est. 1952, Oxford University) by tracing their coverage in the journal, The Book Collector and enhancing their discoverability within Wikipedia.

Despite advancements in digital access to bibliographic records, the Sandars Readership in Bibliography and the Lyell Readership in Bibliography remain under-represented in online resources. This essay explores efforts to address this gap by adding citations from The Book Collector to Wikipedia, creating new articles, and correcting linkages for lecturers. The essay contextualizes these efforts within the broader history of bibliographic control, from Gutenberg’s printing revolution to Paul Otlet’s Mundaneum and modern tools like WorldCat and Wikipedia. It argues that digital indexes, such as the MLA International Bibliography, do not capture the full scope of these lectures, emphasizing the necessity of human intervention to uncover critical bibliographic scholarship. The project underscores The Book Collector’s role as a vital resource and highlights the limitations of relying solely on online platforms for comprehensive bibliographic research.

“Two Ariadne Threads through the Bibliographic Labyrinth: The Sandars and Lyell Readerships in Bibliography”

I follow two simple Ariadne threads in this essay through the contemporary bibliographic labyrinth that provides digital access to printing and book history. I have searched for citations to the Sandars Readership in Bibliography (est. 1895 at Cambridge University) and the Lyell Readership in Bibliography (est.1952 at Oxford University). I chose these two threads because the concentration of the Sandars and Lyell lectures since their inception has been bibliography and the history of the written record. Also, through my general reading on bibliographic topics over many years I have noted that The Book Collector has been the main reliable source of discerning information about these lectures.

David McKitterick’s The Sandars and Lyell Lectures: A Checklist with an Introduction published in 1983 was the primary resource to identify the lectures until they were listed on university websites and Wikipedia. I found the Wikipedia entries to have many mistakes and omissions.[1]

Despite the rapid development of linked electronic data protocols that exist today, much has been overlooked relating to these two important annual bibliographic events. Throughout 2024 I worked through citations and discussions of the lectures to add dozens of links and several new articles to Wikipedia. This work amplifies the importance of the lectures and makes new connections to the scholarship of bibliography. In general, bibliographic scholars have not created linkages between their work and Wikipedia. This means that new searchers—who rely heavily on Wikipedia— miss more expansive treatments.

When Wikipedia emerged as a heavily used source in the 2000s, I decided I would learn to edit it. I teach courses in library history and rare books librarianship. I began to assign to my students that they also learn to add citations to Wikipedia to enhance the visibility of book and library history.[2]

But first I want to step back and provide a brief review of milestones of bibliographic control over the print record.

“That Horrible Mass of Books”

Printed books have nearly a six hundred year history in Europe since the Biblia Latina was issued by Johann Gutenberg in 1455.[3] Over these six centuries bibliographers, philologists, book historians, antiquarians, indexers, encyclopedists, librarians and documentalists have worked to provide connections to ideas, authors and texts.

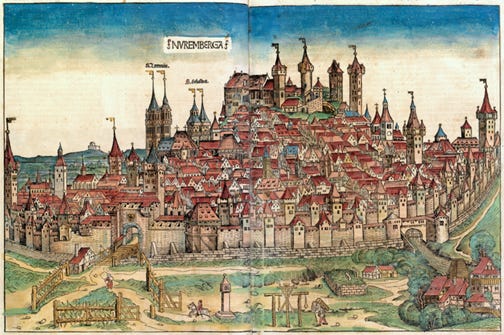

Printed copies of the Nuremberg Chronicle (1493) were acquired and annotated in England as early as 1495.[4] The Nuremberg Chronicle has been viewed as a universal history reflecting concerns of its early Renaissance readers, who needed a framework into which they could put their expanding historical, geographical, and cultural knowledge.[5] As H.S. Bennett discussed in English Books & Readers, 1475-1557 there was a growing population able to read in the vernacular in the fifteenth century.[6] By 1595 a copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle had been annotated in the vernacular to such an extent that the copy that is held at Chetham’s Library in Manchester is viewed “as something like a Wikipedia, compiled from vernacular sources by a diligent and gentle but an ‘unlearned’ reader – to be read and used.”[7]

Woodcut from the Nuremberg Chronicle.Source: File: Nuremberg chronicles - Nuremberga.png - Wikimedia Commons

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries calls for reorganization of the intellectual world grew. [8] In 1545 Conrad Gessner (1515-1565), the “father of bibliography,” envisioned bibliography as “universal,” spanning all the disciplines and all known learned books, in his Bibliotheca universalis.[9] He observed in the preface the “confusing and harmful abundance of books.” Factors such as increasing production and dissemination of books, developing networks of scientific communication, discoveries and innovations in the sciences, and new economic relationships all conspired to produce such quantities of new information that a substantial reorganization of the intellectual world was required.[10]

In 1680 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz declared:

“I fear we shall remain for a long time in our present confusion and indigence through our own fault. I even fear that after exhausting curiosity without obtaining from our investigations any considerable gain for our happiness, people may be disgusted with the sciences, and that a fatal despair may cause them to fall back into barbarism. To which result that horrible mass of books which keeps on growing might contribute very much. For in the end the disorder will become nearly insurmountable.”[11]

The object of this “declaration of intent” was an all-encompassing vision in which the concept “library” acquired a broader sense, becoming an essential element of a general and ambitious plan.[12]

Dirke Werle has discussed the struggle of late Renaissance humanists to deal with the flood of books in the wake of the Gutenberg revolution in Copia Librorum: Problemgeschichte Imaginierter Bibliotheken 1580-1630.[13] (An abundance of books: Problem History of Imagined Libraries). He explored polyhistories like the encyclopedia and pondered the fluid boundaries between book and library, library and world, as well as the long-standing tensions between aspirations towards a bibliotheca universalis and the fear that too many books impair judgment and prevent rather than foster learning. [14]

Encyclopedism, the compilation of works to order knowledge has been explored in Encyclopaedism from Antiquity to the Renaissance where König notes the real significance of printing was the enormous increase in the production of books it enabled, forcing scholars to develop more sophisticated mechanisms for ordering knowledge.[15] The encyclopedic vision was a democratizing, utopian concept. Encyclopedias were viewed as radical co-optations of all knowledge. This was first fully realized in 1728 when Ephraim Chambers published his two-volume Cyclopedia : Or, an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. [16]

Another means of organizing knowledge was catalogs of libraries. Library catalogs began as finding lists for individual libraries. Strout’s overview of the development of library catalogs notes that during the French revolution the new government which had confiscated libraries set up directions for their reorganization in 1791 including instructions for cataloging their collections—the first instance of a national code. [17]

But it was at the British Museum in 1841 that a great advance in bibliographical control was initiated when Anthony Panizzi, Keeper of Printed Books, transformed the library catalog from an inventory into an instrument of discovery in the General Catalogue of Printed Books in the British Museum with Rules for the Compilation of the Catalogue.[18] The General Catalogue was a presentation of a world of books, particularly its English subset, motivated by “the recognition that a comprehensive map of that larger community would support research efforts that, by their nature, could not be anticipated. It served both an historical and documentary function, but also a constituting function, producing that collection in a single space where it could be explored.”[19]

Cumulated indexes of journals go back as far as the first volume of the Philosophical Transactions (London: 1665-67), published under the auspices of the Royal Society of London including a subject index.[20]

Efforts to identify bibliographies of the world were undertaken by Julius Petzholdt (1866) and Theodore Besterman (1939).[21] Although these were formidable compilations they were not used a great deal once printed dictionary catalogues of great libraries were distributed.[22] Something between 80,000 and 100,000 volumes were examined by Besterman at the British Museum alone.[23]

Paul Otlet and the Mundaneum

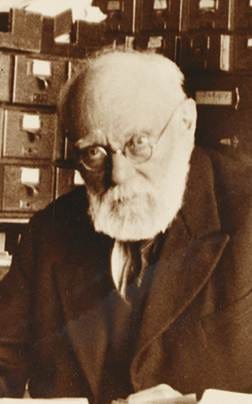

At the beginning of the twentieth century two Belgians looked to encyclopedism in a different configuration to define philosophies of connected world information. Paul Otlet (1868-1944) and Henri La Fontaine (1854-1943) defined the need for an international information handling system embracing everything from the creation of an entry in a catalogue to new forms of publication, from the management of libraries, archives, and museums as interrelated information agencies to the collaborative development of a universal encyclopedia codifying all of man's hitherto unmanageable knowledge. [24] The idea of documentation as a field of study and a professional occupation originated in their work.

Paul Otlet in 1937: Source : File : Paul Otlet à son bureau.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

In 1895 Otlet and La Fontaine established the International Institute of Bibliography (IIB) so that the flow of information would be captured as a cohesive whole, giving it “encouragement and a system in order to emerge.” [25] Otlet’s goal was to create a universal bibliography of all published knowledge, the Repertoire Bibliographique Universel.[26]

Photograph of the staff of the Le Répertoire Bibliographique Universel vers 1900 (International Institute of Bibliography) writing and classifying records- 1900. Source : : File : Le Répertoire Bibliographique Universel vers 1900.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

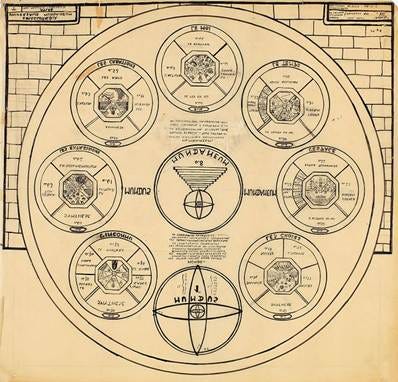

The projects evolved into the Mundaneum, a vast "city of knowledge" that opened its doors to the public in 1921. It was intended to be more than a networked library. Otlet envisioned it as a principal component of a much vaster scheme to build a utopian World City. At its peak, the Mundaneum contained sixteen million cards. Otlet developed his conception of bibliography into what he called "documentation" – going beyond books, journals, catalogs, and libraries to embrace a new system of all documents, whatever their format, that contributed to knowledge and understanding.[27]

Planche de l'Atlas Monde. Source: File: Atlas Monde - Mundaneum.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

During the interwar period, Otlet envisaged the project of building a Cité mondiale in collaboration with Le Corbusier, whose objective was to unite people through a universal civilization, considered a "world bridge." In 1934, the Belgian government cut off funding and the offices were closed.

H.G. Wells, Otlet, and La Fontaine (who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1913) attended the World Congress of Universal Documentation in Paris 1937. Wells' concept of the World Brain included his presentation at the World Congress on a "permanent encyclopedia."[28] It was one of the final hopeful events held under the auspices of the League of Nations, specifically its Organization for International Intellectual Cooperation.[29]

The Congress focused on the potential of microfilm for information storage and retrieval, with a series of speakers— including Otlet, who urged taking advantage of microfilm to facilitate the global exchange of scholarly information. [30] "In parting company, the participants unanimously declared that this Congress marked one of the most important steps in the history of documentation." [31] Discussions at the World Congress have been viewed as forerunners of Wikipedia. [32]

The collection at the Mundaneum remained untouched until 1940, when Germany invaded Belgium. The Germans forced Otlet and his colleagues to find a new home. They reconstituted the Mundaneum as best as they could, and there it remained until it was forced to move again in 1972, after Otlet's death.

Otlet has been remembered. In 1990 W. Boyd Rayward published International Organisation and Dissemination of Knowledge : Selected Essays of Paul Otlet. [33] Today the Mundaneum exists in Mons, Belgium as a non-profit organization with exhibition space, website and archive. [34]

World Wide Web, WorldCat and Wikipedia

After World War II Vannevar Bush wrote the essay, “As We May Think,” in which he presented the idea of the memex, an analog device to manage information -- mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility.[35] And this concept has largely come to be realized today after creation of the World Wide Web, the automation and networking of library records, journal databases and Wikipedia.

During the early 1950s libraries automated access to their collections using punched cards and microfilm before converting existing card catalogues into machine-readable form.[36] Nicolas Barker, writing on libraries and national heritage in The Book Collector predicted that better deployment of computer-linked catalogs would be a means to coordinate the bibliographic records of heritage institutions. [37]

And of course, Barker was right. The accomplishments post-World War II to consolidate bibliographic records have been a dizzying technological march through integrated library systems, bibliographic utilities, meta-searching and linking of content.[38] The rapid computerization of library bibliographic records and serial databases into various computer configurations moved retrieval from paper or microfilm to electronic systems accessible by a desktop computer or mobile phone. [39] The online encyclopedia, Wikipedia, has superseded all prior encyclopedia initiatives.

WorldCat, the electronic union catalog, a product of OCLC (Online Computer Library Center) founded by Frederick Kilgour,[40] had millions of searches in 2023 in 6,500 languages in 135 scripts.[41] It also includes the Open WorldCat program that makes library collections and services visible and available through search engines and provides a central connection between the shared information of the library network and the Web.[42]

Many trace Wikipedia’s heritage to the 20th century's encyclopedism.[43] But the bibliographic and digital frameworks developed by librarians make slight difference to the millions of people who consult Wikipedia each day. [44] It is the most used source of academic knowledge worldwide. The WorldCat database has now integrated its citation tool through the OCLC Linked Data initiative so that Wikipedia editors can type in an ISBN and get back a Wikipedia-ready book citation. [45] Journals cited in Wikipedia articles reach the largest general audiences. The citation impact of Wikipedia references is the current focus of research and findings are that it is impactful on scholarship that is cited.[46]

Sandars Readership in Bibliography and the Lyell Readership in Bibliography: Discoverability

With all these achievements in consolidating bibliographic records and encyclopedic facts I thought what is missing? How would we even know?

A study by B. Luyt made the same observation: “Thwarted by paywalls, not understanding the need to contextualize sources, and permeated by an ideology that sees the online world as containing all that is of value means that there is little or no incentive for users to explore original sources.”[47]

My academic career began before the online world. I had experience of using physical books and journals at the University of Chicago, Regenstein Library, a very large library.[48]

I have experienced the automation of records and indexes. I have graded student papers for decades. I have noted since automation that while students still write acceptable papers, their base of sources has been largely limited to material that is available online.

This leads to considering “discoverability” --how users find information. From search engines to Wikipedia to digital libraries, the ability of platforms to sift through millions of information objects and select the most relevant content is crucial. [49] But what if the information is not easily accessed online? This means that over time there will be fewer citations to publications that are not purchased by libraries or are behind paywalls.

Two Ariadne threads through the digital bibliographic record

I followed two simple Ariadne threads through the digital bibliographic record (WorldCat, periodical indexes) for entries or citations to the Sandars Readership in Bibliography and the Lyell Readership in Bibliography.

I checked the MLA International Bibliography which uses contextual indexing and a faceted taxonomic access system for both the Lyell and Sandars Lectures. I retrieved fewer than forty citations that referenced either the Lyell or Sandars lectures. They were scattered in many different journals (outside of The Bodleian Library Record).

The American Historical Review (1961, 1994, 2002)

The Antiquaries Journal (1960)

Ben Jonson Journal (1999)

The Cambridge Quarterly (2005)

Eighteenth-Century Studies (1993)

English Studies (2001,2011)

Essays in Criticism (2003)

Irish Historical Studies (1991)

Journal of American Studies (1989)

The Journal of Theological Studies (1961)

The Library: The Transactions of the Bibliographical Society, (1965 ,2009, 2022)

Library & Information History (2021)

Medieval & Renaissance Drama in England (2001)

Modern Language Review (2001)

Notes and Queries (1991, 2004)

The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America (1965, 1984)

The Pennsylvania Magazine of History (1989)

Princeton University Library Chronicle (2003)

Renaissance Quarterly (1971)

Recherches de théologie ancienne et médiévale, (1961)

The Review of English Studies (1961, 1993, 2003, 2010)

Studies in Bibliography (2002)

Speculum (1961, 2010)

Theologische Literaturzeitung (2013)

Variants (2016),

The Wordsworth Circle (1994)

Analyzing The Book Collector for discussions about the Sandars Readership in Bibliography and the Lyell Readership in Bibliography

Because I knew from subscribing and reading The Book Collector that the Sandars and Lyell lectures had been covered in review essays or otherwise discussed I realized that the only way to identify additional content about these lectures was to review the archives of The Book Collector. When I did this, I was able to add 117 citations from The Book Collector to various articles in Wikipedia about the two lectures. I did this by reading every issue. I found, despite the rapid development of linked data, that without a human eye much is missed.

Then I did five things to add links and new essays in Wikipedia to amplify the importance of the Sandars and Lyell lectures to make connections to the scholarship of bibliography.

First--there was no Wikipedia page for James Patrick Ronaldson Lyell, whose will established the Lyell Readership in Bibliography at Oxford so I wrote it on April 29, 2024.

Second--there were Wikipedia pages for the Sandars Readership in Bibliography and the Lyell Readership in Bibliography, but many lecturers were not linked to their Wikipedia pages because the lecturers’ Wikipedia page did not use the established name of the lecturers. I corrected these at Wikipedia and made the linkages.

For example, “Alan Noel Latimer Munby ,“ was listed as “A.N.L. Munby” so there was no link to him. I created them. There were others. Table 1 is a list of Sandars and Lyell Lecturers whose names did not link to their Wikipedia pages because the names were incorrectly recorded.

Table 1.

Lyell and Sandars Lecturers Linked to their Wikipedia Pages from the Lyell and Sandars Wikipedia Pages

Alexander, J. J. G.

Barker, Nicolas

Beal, Peter

Bennett, Henry Stanley

Carley, James

Carter, Harry Graham

Carter, John

Clark, John Willis

Cockerell, Sydney Carlyle

de Hamel, Christopher

Dickins, Bruce

Foxon, David

Gaselee, Stephen

Goldschmidt, Ernst Philip

Greg, W.W.

Hobson, Anthony

Johnson, Gordon

Ker, Neil Ripley

King, Alexander Hyatt

McKenzie, Donald Francis

McKerrow, Ronald Brunlees

McLean, Ruari

Morrison, Stanley

Munby, Alan Noel Latimer

Nixon, Howard

Pearson, David

Pollard, Graham

Pollard, Mary

Ratcliffe, Frederick William

Raven, James

Reeve, Michael

Roberts, Colin Henderson

Secord, James A.

Shackleton, Robert

Simmons, John Simon Gabriel

Sparrow, John

Stearn, William T.

Tyacke, Sarah

Williams, Harold Herbert

Wolf, Edwin

Third, some lecturers did not have Wikipedia pages at all and so I wrote several: Philip Hofer, Simon Nowell-Smith and Michael F. Suarez. (There are many more that need to be written).

Fourth, in many cases, even if there was a Wikipedia page for the lecturer, their appointment as a Sandars or Lyell Lecturer was not included on their Wikipedia page, so I added that information and linked back to the lecture pages. Table 2 is a list of the lecturers I linked:

Table 2

Lyell and Sandars Lecturers added to the Wikipedia pages of Lecturers

Alexander, J. J. G.

Barker, Nicolas

Beal, Peter

Bennett, Henry Stanley

Carley, James

Carter, Harry Graham

Carter, John

Clark, John Willis

Cockerell, Sydney Carlyle

de Hamel, Christopher

Dickins, Bruce

Foxon, David

Gaselee, Stephen

Goldschmidt, Ernst Philip

Greg, W.W.

Hobson, Anthony

Johnson, Gordon

Ker, Neil Ripley

King, Alexander Hyatt

McKenzie, Donald Francis

McKerrow, Ronald Brunlees

McLean, Ruari

Morrison, Stanley

Munby, Alan Noel Latimer

Nixon, Howard

Pearson, David

Pollard, Graham

Pollard, Mary

Ratcliffe, Frederick William

Raven, James

Reeve, Michael

Roberts, Colin Henderson

Secord, James A.

Shackleton, Robert

Simmons, John Simon Gabriel

Sparrow, John

Stearn, William T.

Tyacke, Sarah

Williams, Harold Herbert

Wolf, Edwin

Fifth, I added citations to fifty-seven additional items of information to the Sandars and Lyell Lecture pages including citations to some that had been published.

I chose these threads because the only frequent coverage of the Sandars and Lyell Lectures was in The Book Collector. Exploring far greater coverage in the journal compared to identification using digital indexes demonstrates that online resources are not yet comprehensive, especially for bibliographic topics.

Conclusion

Efforts to manage knowledge show us that from the days of the first printed books there have been many efforts to organize access. Encyclopedias, printed library catalogs, integrated cataloging systems, the MLA Bibliography, Otlets’ Mundaneum, even Worldcat fall short in capturing the complete bibliographic footprint of these important lectures.

In “Dreams of the Universal Library” Hui reviewed the transition from Leibniz’s medievalism to the secular, disenchanted age of Borges, with the dream of Borges’ total library transcending the history of ideas and information management. [50] Thinking of the book (as codex) in terms of contingency rather than permanency raises questions relating to literature which we can only begin to glimpse. Sauerberg has proposed the concept of a Gutenberg Parenthesis from the beginning of print to digitized textuality.[51]

But as I discovered scrolling through the archives of The Book Collector, which is digitized, but not searchable in full-text outside of subscriptions, many important discussions and serious citations to the Sandars and Lyell Lectures are lost to those who think that online is everything.

[1] McKitterick, David. 1983. The Sandars and Lyell Lectures: A Checklist with an Introduction. New York: Jonathan A. Hill.

[2] McCook, Kathleen de la Peña. (2014). "Librarians as Wikipedians: From Library History to “Librarianship and Human Rights.” Progressive Librarian 42 :61 - 81.

[3] Biblia latina, 42 lines. ib00526000. Mainz: Printer of the 42-line Bible (Johann Gutenberg) and Johannes Fust, about 1455]. British Library. 1980. “Incunabula Short Title Catalogue.” London.

[4] Payne, M.T.W. “Robert Fabyan and the Nuremberg Chronicle.” Library 12, no. 2 (2011): 164–69; Schedel, Hartmann. (2013). Chronicle of the World 1493: The Complete Nuremberg Chronicle. Ed. Stephan Füssel. Trans. Ishbel Flett. Köln: Taschen, 2013; Wilson, Adrian, and Joyce Lancaster Wilson. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. Amsterdam: Nico Israel, 1976.

[5] Wagner, Bettina. Worlds of Learning: The Library and World Chronicle of the Nuremberg Physician Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514). Munich: Allitera Verlag, 2015.

[6] Bennett, H. S. 1952. English Books & Readers, 1475-1557: Being a Study in the History of

the Book Trade from Caxton to the Incorporation of the Stationers’ Company. Cambridge

[England]: University Press

[7] Adamova, N. (2021). "Chapter 8 Rural Readings of Sacred History: The Nuremberg Chronicle and Its Lancashire Readers" pp. 157-177. In Communities of Print. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

[8] Rosenberg, Daniel. “Early Modern Information Overload.” Journal of the History of Ideas 64, no. 1 (2003): 1–9.

[9] Gessner, Conrad (1545). Bibliotheca Universalis, sive Catalogus omnium Scriptoum locupletissimus, in tribus linguis, Latina, Græca, & Hebraica; extantium & non extantium, veterum et recentiorum in hunc usque diem ... publicatorum et in Bibliothecis latentium, etc. Zurich: Christophorum Froschouerum.

[10] Blair, Ann. “The Capacious Bibliographical Practice of Conrad Gessner.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 111, no. 4 (2017): 445–68; Blair, Ann. 2003. Reading strategies for coping with information overload, ca.1550-1700. Journal of the History of Ideas 64, no. 1: 11-28.

[11] Leibnitz, Gottfried W. 1680 “Precepts for advancing the sciences and arts,” p. 29. Reprinted in 1951: Leibniz: Selections. Edited by Philip P. Wiener. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

[12] Palumbo, Margherita. “Leibniz as Librarian.” In The Oxford Handbook of Leibniz. Oxford University Press, 2018.

[13] Werle, Dirk. 2007. Copia Librorum : Problemgeschichte Imaginierter Bibliotheken 1580-1630. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

[14] Johnson, C. (2008). [Review of Copia librorum. Problemgeschichte imaginierter Bibliotheken 1580–1630, by D. Werle]. Renaissance Studies, 22(5), 752–754.

[15] König, Jason, and Greg Woolf. (2013) Encyclopaedism from Antiquity to the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

[16] Chambers, Ephraim. 1728. Cyclopædia : Or, an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences ; Containing the Definitions of the Terms, and Accounts of the Things Signify’d Thereby, in the Several Arts, Both Liberal and Mechanical, and the Several Sciences, Human and Divine: The Figures, Kinds, Properties, Productions, Preparations, and Uses, of Things Natural and Artificial ; the Rise, Progress, and State of Things Ecclesiastical, Civil, Military, and Commercial: With the Several Systems, Sects, Opinions, &c. among Philosophers, Divines, Mathematicians, Physicians, Antiquaries, Criticks, &c. the Whole Intended as a Course of Antient and Modern Learning. Compiled from the Best Authors, Dictionaries, Journals, Memoirs, Transactions, Ephemerides, &c. in Several Languages. In Two Volumes. London: Printed for James and John Knapton, etc.; Yeo, Richard. 2003. “A Solution to the Multitude of Books: Ephraim Chambers’s ‘Cyclopaedia’ (1728) as ‘the Best Book in the Universe.’ ” Journal of the History of Ideas 64 (January): 61–72.

[17] Strout, Ruth French. “The Development of the Catalog and Cataloging Codes.” The Library Quarterly (Chicago) 26, no. 4 (1956): 254–75.

[18] British Museum. 1841. Catalogue of Printed Books in the British Museum. Volume I. Edited by Anthony Panizzi. London: Printed by order of the Trustees, J.B. Nichols and Son…. The rules were pp. v-ix.; Guerrini, Mauro, and Stefano Gambari. ’Definite Cataloguing Rules Set down in Writing’: Le Rules Di Antonio Panizzi e Le Manifestazioni Del Catalogo.” JLIS.It : Italian Journal of Library and Information Science 14, no. 2 (2023): 93-99; Chaplin, A. H. 1987. GK: 150 Years of the General Catalogue of Printed Books in the British Museum. Brookfield, Vt.: Scolar Press.

[19] Griffiths, Devin. “The Radical’s Catalogue: Antonio Panizzi, Virginia Woolf, and the British Museum Library’s ‘Catalogue of Printed Books.’” Book History 18, no. 1 (2015): 134–65.

[20] Balay, Robert. 2000. Early Periodical Indexes: Bibliographies and Indexes of Literature Published in Periodicals before 1900. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press.

[21] Minter, Catherine J. "Julius Petzholdt and the North American Library World: Transatlantic Circulation of Bibliothecal Knowledge in the Nineteenth Century" Libri, vol. 73, no. 4, 2023, pp. 335-344; Besterman, Theodore. A World Bibliography of Bibliographies, Volume I A-L [Volume II M-Z Index\ Printed for the Author at the University Press, Oxford, and Published by him at 98 Heath Street, London, N.W. 3. Sole Agents for North and South America. The H. W. Wilson Company . . . New York, N. Y. 1939 [-1940].

[22] Wadsworth, Robert Woodman. 1988. “Bibliographie Der Nationalen Bibliographien/A World Bibliography of National Bibliographies. Friedrich Domay.” The Library Quarterly 58 (3): 299–301.

[23] Jaryc, M. (1942). [Review of A World Bibliography of Bibliographies, By Theodore Besterman Volume I A-L [Volume II M-Z Index], by Theodore. Besterman]. The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 36(4), 321–324.

[24] Rayward, W. B. (1994). Visions of Xanadu: Paul Otlet (1868-1944) and hypertext. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 45, 235–250.

[25] Wright, Alex (2014). Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age. Oxford; New York: OUP, USA.

[26] Otlet, Paul. 1934. Traité de Documentation : Le Livre Sur Le Livre, Théorie et Pratique. Bruxelles: Editiones Mundaneum.

[27] Grolier, Eric de. Paul Otlet, Pionnier de la documentation et de la coopération internationale. La Documentation en France, novembre 1945, no 07: 207-268.

[28] Smith, L. C. (1991). "Memex as an Image of Potentiality Revisited." In J. M. Nyce, & P. Kahn (Eds.), From Memex to Hypertext: Vannevar Bush and the Mind's Machine (pp. 261-286). Academic Press.

[29] Rayward, W. Boyd. (1983) “The International Exposition and the World Documentation Congress, Paris 1937.” The Library Quarterly 53.3 (1983): 254–268.

[30] Ibid. Wright.

[31] Le Congrns Mondial de la Documentation Universelle." Congres Mondial de la Documentation Universelle, Paris, August 16-21, 1937. Compte rendu des travaux. Paris : Secretariat, 1937.

[32] Reagle, Joseph Michael ; Lessig, Lawrence (30 September 2010). Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia. MIT Press.

[33] Otlet, Paul, and W. Boyd Rayward. 1990. International Organisation and Dissemination of Knowledge: Selected Essays of Paul Otlet. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

[34] Gillen, Jacques. (2023). "Mundaneum: Machine to Think the World": A New Permanent Exhibition." Blog of the IFLA Library History SIG (May 10, 2023). iflalibraryhistorysig.blogspot.com; mundaneum.org/en/

[35] Bush, Vannevar. (1945). "As We May Think". The Atlantic Monthly 176 (1) (July): 101–108.

[36] Black, Alistair. 2007. “Mechanization in Libraries and Information Retrieval: Punched Cards and Microfilm before the Widespread Adoption of Computer Technology in Libraries.” Library History 23 (4): 291–99

[37] Barker, Nicolas. (1985). "Libraries and the National Heritage: Two Views from Europe. " The Book Collector 34 (no 2): Summer: 145-172; Krummel, D. W. “Guides to National Bibliographies: A Review Essay.” Libraries & Culture 24, no. 2 (1989): 217–30.

[38] Bracke, P.J., McNeil, B., Kaplan, M. (2023). “Library Automation and Knowledge Sharing.” In: Nof, S.Y. (eds) Springer Handbook of Automation: 1285-1298. Springer Handbooks. Springer, Cham.

[39] Zumer, Maja. National Bibliographies in the Digital Age: Guidance and New Directions. 1st ed. Munchen: K.G. Saur, 2009.

[40] Kilgour, Frederick G. “A Personalized Prehistory of OCLC.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 38, no. 5 (1987): 381–84.

[41] OCLC Annual Report 2022–2023. https://www.oclc.org/en/annual-report/2023/home.html

[42] Nilges, Chip. 2006. “The Online Computer Library Center’s Open WorldCat Program.” Library Trends 54 (3): 430–47.

[43] Burke, Peter. A Social History of Knowledge. II, from the Encyclopedie to Wikipedia. Cambridge, [Massachusetts]; Polity, 2012; Reagle, Joseph M., and Jackie L. Koerner. (2020). Wikipedia @ 20: Stories of an Incomplete Revolution. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

[44] For statistics on use see en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia: Statistics; Lih Andrew. (2009). The Wikipedia Revolution: How a Bunch of Nobodies Created the World's Greatest Encyclopedia. 1st ed. New York: Hyperion.

[45] OCLC. 2024. “Linked Data: The Future of Library Cataloging.” Dublin, OH: OCLC.://doi.org/10.25333/71w4-vq71 ; Jake Orlowitz. “The Wikipedia Library: The Biggest Encyclopedia Needs a Digital Library and We Are Building It.” JLIS.It : Italian Journal of Library and Information Science 9, no. 3 (2018).

[46] Teplitskiy, Misha, Grace Lu, and Eamon Duede. (2017). “Amplifying the Impact of Open Access: Wikipedia and the Diffusion of Science.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 68.9 (2017): 2116–2127.

[47] Luyt B. Representation and the problem of bibliographic imagination on Wikipedia. Journal of Documentation. 2022;78(5):1075-1091.

[48] University of Chicago Library. www.lib.uchicago.edu/about/thelibrary/

[49]Woolcott, L., & Shiri, A. (Eds.). (2023). Discoverability in Digital Repositories: Systems, Perspectives, and User Studies (1st ed.). Routledge.

[50] Hui, Andrew. “Dreams of the Universal Library.” Critical Inquiry 48, no. 3 (2022): 522–48; Jorge Louis Borges, “The Total Library,” trans. Eliot Weinberger, in Selected Non Fictions, trans. Esther Allen, Suzanne Jill Levine, and Weinberger, ed. Weinberger (New York, 1999), pp. 214, 216.

[51] Sauerberg, Lars Ole. “The Gutenberg Parenthesis - Print, Book and Cognition.” Orbis Litterarum 64, no. 2 (2009): 79–80.

Kathleen de la Peña McCook is distinguished university professor of librarianship, School of Information, University of South Florida in Tampa, Florida.

"[L]ost to those who think that online is everything"

I'm romantic enough to think there's an endpoint to this phenomenon.

In five years our bookshelves will still be full, and the "world wide web" will be just paywalled chatbotted slop. And librarians will begin again, as mentors, to help people learn (or relearn) how to sit quietly and read a book.

Thanks for all you do!

The importance of libraries and librarians cannot be over-stated. Living in a small town with a city council bent on downsizing or eliminating our library is problematic. One of our city councilors wondered why anyone needed a library when "if I need a book, I order it on Amazon".

Information I have accessed though the Minnesota State Library is not always available on Wikipedia or even the Internet.